How do you prepare for rehearsals with fellow musicians? When playing chamber music or concertos, it’s essential to know everyone else’s part well enough to come in on cue and play together. Pianists play from a full score (or at least a piano reduction in the case of concertos), enabling us to see what everyone else is doing. Still, it takes a lot of practice to get used to playing together. Playing in concert can actually be disconcerting!

How, then, can we get used to playing together with other musicians? It should come as no surprise that the best way to learn to play together is to play together, and to play together frequently. However, this is a luxury that many musicians simply don’t have. Furthermore, the more musicians there are in an ensemble, the harder it is to schedule rehearsals in general. What’s more, for professional ensembles, rehearsals are expensive and time is strictly limited.

Technology to the rescue

Nowadays, technology can allow us to rehearse virtually with an ensemble. A company called Music Minus One first created this possibility. Founded way back in 1950 (!), this company made recordings of chamber music in all permutations, with one musician missing in each of them. If you played piano in a piano quartet, you could play along with the version with all the string instruments. If you played cello in the same piano quartet, you could play along with a version containing all instruments except cello. The company is still operating today and has a catalog of hundreds of works.

When I was a student, I was happy to make use of the newer technology that was then available. In my practice room at Penn State there was an old Steinway grand and a new Yamaha upright with Disklavier technology. This was modern player piano technology that made it possible to record a performance and have the piano play it back. The keys and pedals would move as if a ghost were playing. The recording wasn’t perfectly accurate, but it was very useful, especially for the purpose of rehearsing. For example, singers could rehearse with a virtual accompanist and even change the key to fit their vocal range.

My professor, Dr. Steven Smith, kindly recorded the orchestral reductions of concertos I studied. This enabled me to practice the entrances and timing with the Disklavier. I could slow down the accompaniment and gradually work up to performance tempo. By the time I got to my first rehearsal with orchestra, I was already comfortable playing together with them thanks to practicing with the virtual accompaniment.

Modern technology

Not too many musicians have modern player piano technology at their disposal, however. Buying a piano equipped with this technology is a major investment, pianos need space and maintenance.

But pretty much everyone has a computer these days. Even if you only have a smartphone, there’s an innovative solution: Imagine turning any ensemble recording into your own personal Music Minus One-type play-along recording! There are new software tools that can remove individual instruments from recordings.

At this point it’s important to set reasonable expectations. These tools will invariably perform a bit better with some recordings compared to others, and different tools give slightly different results. For our purpose of turning a recording into a virtual accompanist, we just need these tools to be “good enough.” Fortunately they’re already much more than that.

Lalal.ai

Pronounced “lala-lie,” the name derives from “lala” (as in singing “la-la”) and AI (as in artificial intelligence). Lalal.ai is a web app (in other words, a website that runs software in the background) that uses artificial intelligence to separate instruments from existing recordings.

In theory, this should be impossible. Mixing audio is like baking a cake: Once you've cracked an egg and mixed it with flour, sugar, and oil, there's no separating them again. Audio is also a one-way street: Once piano, strings, winds, brass, and percussion have been mixed, there's no going back. The point of no return is the “downmixing” process, when the audio from many microphones are combined and mixed into the left and right channels we ultimately hear on our headphones or speakers.

Removing an instrument from an already down mixed recording may seem like magic, like removing an egg already mixed into cake batter, but with artificial intelligence this actually becomes possible (at least for audio).

How it works

Visit Lalal.ai and upload a recording. Ideally you’d upload a higher-resolution recording rather than one that has been compressed using MP3, AAC or similar tools. These are “lossy” compression algorithms, meaning that they discard most of the information on your recording. They’re also clever in that they only throw away information that in theory we can’t hear anyway, but there’s a limit. Once the information is gone there’s no way to restore it, so it’s best to work with the original high-resolution audio if possible.

After uploading, your recording will be processed and you can download the results. These are split into two files: the instrument that was removed and everything else.

Test case: Solo piano

I performed a bit of a “mean” test by inputting a solo piano recording. The file was not compressed (48 kHz, 24 bits for the tech geeks). A perfect algorithm would recognize that piano is the only instrument and split the solo piano recording into two parts: the piano and complete silence. The piano part would ideally consist of the exact original recording (because the recording input to the algorithm is solo piano) and silence (i.e., everything else, which is to say nothing else).

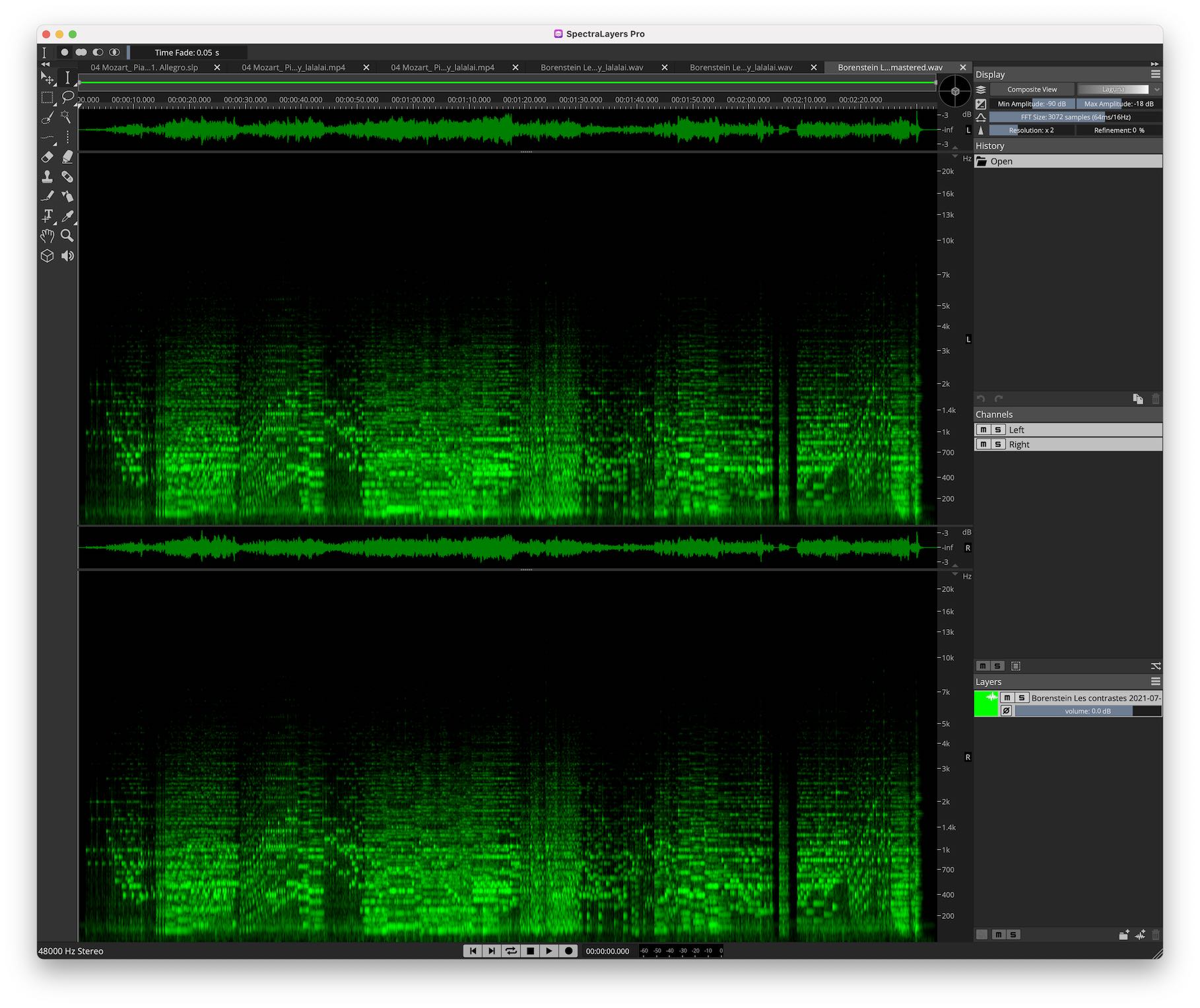

Original solo piano recording

Original solo piano recording

The result? To my surprise, it performed extremely accurately. The piano part was recognized and extracted almost perfectly, and the other part consisted of just a few minor artifacts. Unless you compared the extracted piano recording with the original and listened very closely, you probably wouldn’t notice anything was missing.

Solo piano as recognized by Lalal.ai

Solo piano as recognized by Lalal.ai

Artifacts from solo piano recording incorrectly recognized by Lalal.ai

Artifacts from solo piano recording incorrectly recognized by Lalal.ai

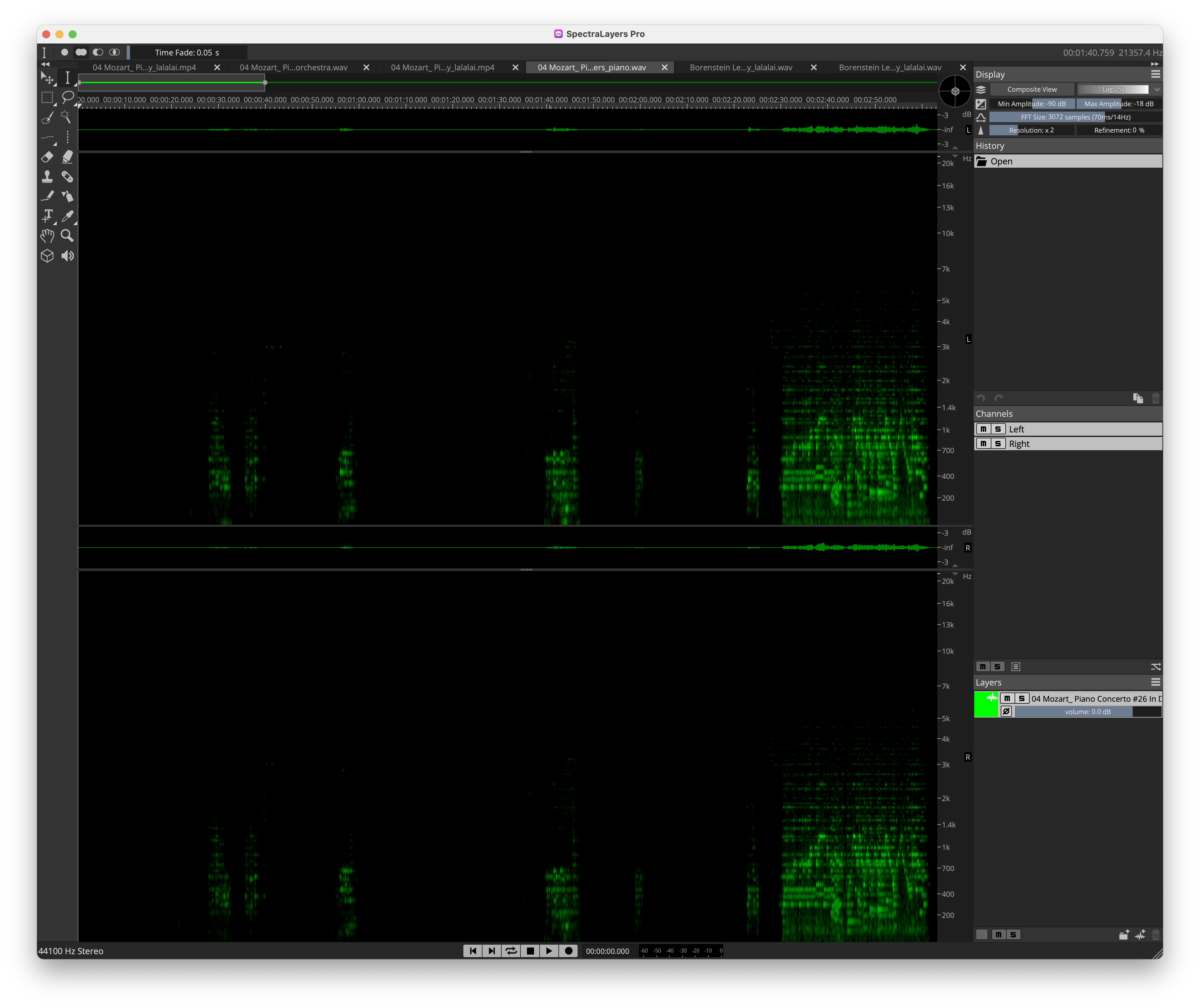

Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 26 in D major, K. 537

Next, I tried a concerto I’m working on: Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 26 in D major, K. 537, in my mentor Paul Badura-Skoda’s stylistic completion. For this test I tried different software, Steinberg’s SpectraLayers Pro version 8. This is a heavy duty, professional audio restoration tool designed for recording engineers; it was never intended for musicians who aren’t themselves sound engineers. It also has many features that go well beyond extracting instruments from mixed recordings. In short, it’s a godsend for engineers but overkill and overly complicated for most musicians, like taking a sledgehammer to crack a nut. Still, it’s worth comparing how it performs the extraction process with lala.ai.

Piano incorrectly "heard" in orchestral introduction by SpectraLayers Pro 8 (the solo piano entry comes at 2:30)

Piano incorrectly "heard" in orchestral introduction by SpectraLayers Pro 8 (the solo piano entry comes at 2:30)

Piano incorrectly "heard" in orchestral introduction by Lalal.ai (the solo piano entry comes at 2:30)

Piano incorrectly "heard" in orchestral introduction by Lalal.ai (the solo piano entry comes at 2:30)

1st mvt., tutti:

- Neither algorithm is perfect, but SpectraLayers is more effective.

- Lalal.ai "hears" more piano during the orchestral introduction, even though only the orchestra plays.

1st mvt., mm. 105–106 (3:10): Compare SpectraLayers Pro 8 to Lalal.ai:

- SpectraLayers (at its default setting) turns out to be too aggressive. You can hardly hear the strings in the accompaniment as a result.

- With Lalal.ai, the strings are clear. Here, Lalal.ai outperforms SpectraLayers.

This isn’t meant to be a shootout between competing algorithms, especially since they serve different markets and aren’t really competitors.

That said, here are a few notes which you might find helpful:

- Technically, SpectraLayers is arguably somewhat cleaner at extracting piano but at the expense of sometimes being too aggressive (at its default setting).

- For the purpose of rehearsing music with a virtual accompanist, Lalal.ai is more helpful with timing because you can just barely hear the piano from the original recording. This helps more for setting the tempo when practicing a passage, since the piano you're practicing on will drown out the "ghost" of the piano from the processed file.

- Overall, both algorithms are remarkably effective. I'd recommend SpectraLayers only to audio engineers who need to do "surgical" work on sound files. After all, this is the audience for which this feature-laden, more powerful software was designed. To musicians looking to practice virtually with other instrumentalists, Lalal.ai is an ideal tool thanks to its web interface and ease of use.

Conclusion

There's of course a lot that these tools cannot do. Unlike real musicians, they can't listen and respond to your playing. They can't respond to your tempo, your phrasing, and your timing changes. It's therefore risky to rely too much on this technology. The purpose of this sort of practice is only to get comfortable with what all the other musicians are doing, to practice your entrances, and to make sure you're playing in time while listening to the whole ensemble. This is a wonderful tool that can help you prepare for your first rehearsal with fellow musicians. You will have accomplished much of the groundwork and can spend the rehearsal time on your interpretation. After all, that's what making music is all about.

P.S. Another option for playing with virtual musicians is the app Tomplay, which is a modern version of the Music Minus One recordings. Tomplay is a fully featured, multi-platform app that deserves a separate post!

Start Your NEW Piano Journey

Sign up below and each week for the next year, I'll send you a conservatory-quality 3- to 5-minute lesson sharing exclusive playing and practice techniques used by concert artists worldwide.

Each lesson has been carefully crafted to meet the needs of players ranging from beginners to the late intermediate level.

As a very special bonus, you'll also receive invitations to join our exclusive live Keys to Mastery™ monthly masterclasses.

We will never sell your information, for any reason.