Capturing the Viennese sound with Bösendorfer and Austrian Audio

How do you capture the grandeur of a concert grand? Imagine the technological wizardry it takes to compress the whispers and roars of nine or more feet of handmade master craftsmanship into just two tiny ear buds. This magnificent instrument places inordinate demands not only on pianists, but also on recording equipment and engineers alike.

Several aspects of the instrument make capturing its sound so elusive. The first is its sheer size. A standard concert grand is about nine feet long. Some are even bigger: The legendary Bösendorfer Imperial here is a full nine-and-a-half feet (290cm) in length. As if that were not enough, it also has nine extra keys in the bass, making for a full eight octaves. Its massive soundboard, the sonic heart of any piano, is significantly longer and wider than even the sizeable soundboards of standard concert grands.

Another factor that makes a concert grand challenging to record is its extreme tonal range, which eclipses that of an entire orchestra. The bottom A, the lowest of a standard piano’s eighty-eight keys, is deeper even than a double bass. The Bösendorfer Imperial extends all the way to a low C, whose frequency is so low that it’s actually beneath the threshold of human hearing. (We only hear overtones of these lowest keys.) The highest C on a piano is the highest note a piccolo can play.

As if its extreme tonal range did not make it challenging enough to record, a concert grand also has an extreme dynamic range. High-end pianos are engineered specifically to have a very wide dynamic range throughout their tonal range, from barely-there pianissimos to ear-splitting fortissimos. This gives artists as much flexibility as possible to shape the sound, like a painter who has every color and shade available.

Finally, the piano is technically a percussion instrument. Personally, I don't like to think of the piano as a percussion instrument, but technically this is what it is. This has to do with how sound is produced: We pianists do not have any direct contact with the parts of the piano that actually produce the sound, namely hammers striking strings. The hammers immediately bounce off the strings, making for a fast “attack” (this is the acoustics term), as the strings go from motionless to vibrating intensely in a split second.

As you might imagine, these properties of a grand piano present significant technological challenges to microphones too. To capture a grand piano accurately, microphones need to be extremely sensitive and able to handle high sound pressure levels without distortion, all while maintaining a “flat” frequency response. In other words, they shouldn’t over- or under-emphasize low or high notes or anything in between. We almost require our tools to defy the laws of physics.

A crash course on microphones

The heart of a microphone is a vibrating membrane that needs to respond to the slightest changes in sound waves. There are several different main types of microphones, each of which uses a different type of membrane that moves in response to sound waves: Dynamic microphones use a moving coil, like most loudspeakers; ribbon mics use an extremely thin strip of foil; and condenser mics use a capacitor: a fixed backplate combined with a moving diaphragm that picks up sound.

Microphones also have different pickup patterns, more technically called polar patterns. Directional mics only record what is directly in front of them (called a “cardioid” pattern):

Others, like ribbon mics, record what is in front and behind them but reject sound on the sides (called “figure-of-eight”):

Still others record everything around them (“omnidirectional,” or “omni” for short):

There are other patterns too, such as the laser-focused hypercardioid found in so-called “shotgun” mics, or wide cardioid, whose pickup pattern is somewhere between omnidirectional and cardioid.

Each of these types of microphones and polar patterns has its place in a recording engineer’s toolkit, but we’ll focus on condenser microphones since this is the most common type used for studio recordings.

I’ve slowly been keeping my eye out for general-purpose microphones that can be used not just for piano but also for chamber music and singers. This meant limiting my search to large-diaphragm condensers, as they’re called. Small-diaphragm condensers, sometimes called “pencil condensers” because they look like fat pencils, can in theory be more accurate because the smaller membrane can react faster to sound waves, but large diaphragms can lend a striking smoothness to the sound that flatters voices and acoustic instruments.

Also, while most microphones are limited to a single pickup pattern, some large-diaphragm condensers offer switchable patterns. Some small-diaphragm models, like the venerable Schoeps CMC6, use interchangeable capsules with different pickup patterns that can be purchased separately, though the cost can quickly add up.

Sidebar

Budget pick: Professional piano mics under $1000

A former Schoeps repairman, John Peluso, created an excellent similar model, the Peluso CEMC6, also with interchangeable capsules, which offers most of the quality of the CMC6 at a fraction of the price. He told me that he designed them specifically with piano in mind and that they are frequently used by NPR for live broadcasts with Steinway D concert grands. Using these mics I've made many piano recordings over the years that critics have praised for their natural sound. I once did a direct A/B comparison during a live recording session and was surprised to discover how close the Peluso model comes to the Schoeps. The law of diminishing returns applies here: You'll need to be prepared to pay several times the price for the last ten or fifteen percent.

The classic: AKG C414

My search for an all-rounder pair of mics started and nearly ended with a studio classic. For decades, the “go to” all-purpose microphone has been the C414, invented by AKG Acoustics in Vienna. At least one pair can be found in almost every recording studio in the world. The C414 has been through several generations since its debut in 1971. While all of them are objectively excellent professional tools, recording engineers agree almost universally that the original version, with its legendary brass capsule has a magical sound quality that later versions could not match.

The problem with the brass capsule, called the CK12, is that it was exceedingly time-consuming and expensive to make. It could only be made by hand, there was a failure rate of up to fifty percent during the manufacturing process, and by some accounts sometimes only a single microphone could be built on a given day. Clearly this was unsustainable, so AKG sought a tenable alternative. Nylon turned out to be a much more cost-effective material, but it was unable to match the universally praised magical quality of the original brass capsule. That said, nylon did have the decisive advantage of producing consistently reproducible results, in contrast to the more temperamental CK12.

The Holy Grail

Ever since manufacture of the CK12 ceased, there have been attempts to imitate it, including several by AKG's own engineers. Then something dramatic happened: In 2017, AKG Acoustics' corporate owner made the shocking announcement that it would dissolve its corporate headquarters, offices, engineering, and manufacturing facilities in Vienna. The C414 is still being manufactured, now in Hungary to the high standards of the specifications, but they are only serviced at one location in Germany. The world-renowned Viennese company as it was known for decades, which pioneered technological advances in high-end audio, no longer exists.

A startup with three-and-a-half centuries of experience: Austrian Audio

In response, a group of over twenty former AKG engineers from the research and development team, who were the heart of the dissolved Viennese company, formed a startup that same year. This was the birth of Austrian Audio.

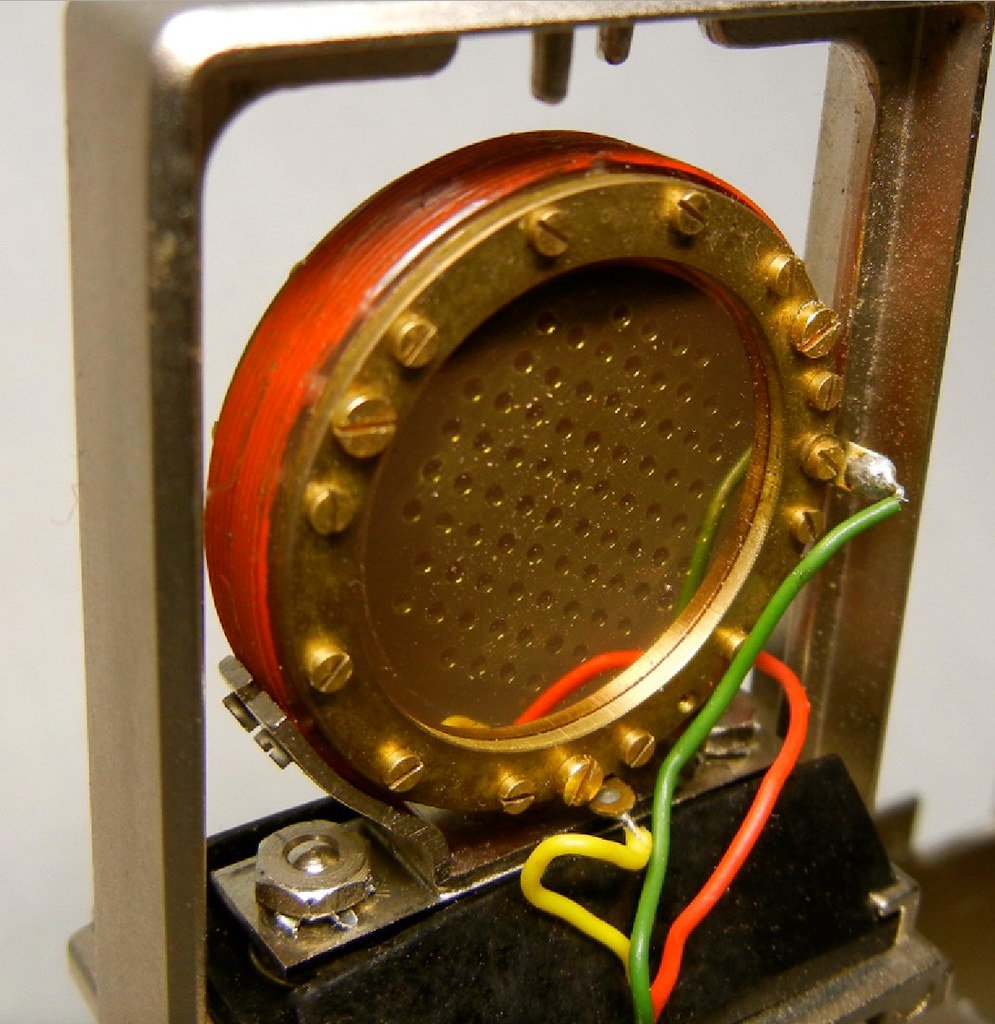

They were nothing if not ambitious: The first engineering task they set for themselves was no less than to recreate the Holy Grail. They collected, analyzed, and tested the best CK12 brass capsules they could find. The result was an evolution of the CK12, this time using a ceramic capsule. They call it the CKR12, and it is identical in size to AKG’s original brass capsule. And like its predecessor, the capsule is once again handmade in Vienna.

The flagship: OC818

Austrian Audio’s showpiece is the OC818, a microphone that uniquely combines the virtues of an industry classic with genuine technological advancements. It's no coincidence that the name is similar to the C414. This new microphone's feature set has been examined in depth elsewhere, but a few innovations are worth highlighting here too:

- The ceramic capsule is so consistent that any two OC818’s can be reliably used as a matched stereo pair. (For the technically minded, all OC818’s are tuned to a maximum deviation from one another of just 1 decibel throughout the entire frequency range, an astonishingly tight tolerance.)

- A Bluetooth module is available that allows for 255 polar patterns controlled remotely via app.

- The mics feature a special dual output mode that can record each diaphragm to a separate channel. This means that a polar pattern can be chosen in post production, and it’s even possible to record in stereo using just one OC818!

Sidebar

Getting creative

Compared to their small-diaphragm cousins, large-diaphragm condensers often exhibit off-axis coloration. This means that the character of the sound coming from the sides and rear of the mic can be inaccurate, similarly to how colors and brightness change when viewing some screens at an angle. The OC818's are rare large-diaphragm condensers that are largely free of such coloration. This means that they can be used in creative ways. For example, a single OC818 could even be placed at a 90-degree angle to a solo instrumentalist and, combined with the dual output mode, recorded in virtual stereo!

For our simpler purpose, we won’t be needing any of these special features. We’ll simply use a pair of OC818’s in cardioid mode. You can try this stereo technique with any directional mic.

ORTF: a “one size fits all” stereo technique?

If you only remember one thing about recording, remember this: There is really no "best"; there are just different tools for different applications. Each professional tool and each method has its place, and a skilled engineer will know the tools that will work well for a given combination of instrument, room, player, and music.

That said, it’s by no means the case that anything goes. True stereo is actually a mathematical phenomenon, and stereophonic recording was invented by the British engineer Alan Blumlein way back in 1931. There are good reasons why standard stereo techniques exist, so these are the best starting points.

There are also many different ways to record a piano. Even an entire course on the subject would just scratch the surface. For now, I’d like to share my personal favorite technique that is as close to “It just works” as possible. This technique is called ORTF, which stands for Office de Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française. This was France’s public television and radio agency for a decade starting in the mid-1960s. This stereo technique was developed there and was named accordingly.

The idea behind the ORTF technique is to simulate human hearing. With our two ears, our brains can locate sounds in two fundamental ways: One is that a sound reaches each ear at slightly different times, and the other is that it reaches each ear with different intensities. A sound coming from the left side reaches the left ear first, and it is louder in our left ear. This is a bit of a simplification, but it is the essence of how our brains locate sound.

There are stereo techniques that rely only on intensity differences and ones that also capture timing differences. They all have their inherent advantages and disadvantages. ORTF effectively combines the best of both worlds, lending recordings a natural soundstage.

Sidebar

Timing vs. intensity

If two directional microphones (in other words, a pair of cardioid or figure-of-eight mics) are placed as close to one another as possible at different angles, sounds will reach the two mics at the same time. This type of stereo technique is called coincident miking, or a coincident pair. There will be no timing differences between the mics since they are at the same place. This results in a very clear and stable stereo image but less sense of the acoustic.

Other stereo techniques, in which microphones are spaced apart, rely on both timing and intensity differences. One such common technique is called AB, which uses two forward-facing omnidirectional microphones spaced at a distance from each other and from the sound source that can be determined by the recording engineer.

ORTF has several advantages compared to other stereo techniques. It simulates the way we hear, partly by placing the mics the same distance apart as our ears are from each other. It also works with many different microphones, as long as they have a cardioid pickup pattern (in other words, they only record what is in front of them). ORTF is also not hypersensitive to placement, and it is relatively easy to set up, especially if you have a stereo bar.

How to set up ORTF

The ORTF technique is simple: Place two cardioid mics seventeen centimeters apart and angle them outward 110 degrees. That’s it! Depending on your mics, there are even special mounts that you can get that will put them in exactly the right position.

The numbers—seventeen centimeters and 110 degrees—are important. These have been scientifically calculated and have stood the test of time. If the mics are too close or the angle too small, the recording will lack a good stereo image. If the mics are too far apart, there will be phasing issues. This means that some frequencies will get canceled out while others will get amplified, heavily distorting the sound of the instrument. If the angle is too large, there will be a “hole in the middle” of the soundstage.

Now that we have the ORTF configuration in place, let's first figure out where to place the mics in relation to the piano. There are limitless possibilities, but in many real-world situations we often don't have the luxury of auditioning many different mic placements. Luckily there is a sweet spot that all Bösendorfer grands I've worked with have, and probably most other grand pianos too. It's right in the curve of the piano. If you cup your ears while someone is playing, you'll be almost certain to hear great clarity throughout the range of the instrument at this spot. In my experience, this position has never failed to yield a professional result. If you're miking a grand piano and don't have time to experiment with many different mic positions and techniques, an ORTF pair at the curve of the piano is almost certain to get you a good result.

There may be other sweet spots too: In my experience both Bösendorfers and Steinways can sound wonderful when recorded from the far end of the piano, though this location doesn't work in every room, especially if the piano is in a corner.

As far as distance to the piano goes, I prefer relatively close miking in order to capture the details of articulation and dynamic nuances that we pianists work so hard to achieve. Placing the outermost microphone approximately on the same plane and level with the straight edge of the piano works well to my ears. If you're in a room with great acoustics, you can place them a bit farther from the piano to capture more of the room sound.

As for the height, about halfway between the rim and the fully open lid is almost certain to work well. You can also angle them downward so that they point directly at the soundboard rather than at the lid. Just be careful that the weight of the mics, especially if you’re using large-diaphragm condensers, doesn’t pull them down.

One "secret" tip: I like to reverse the channels so that the microphone closest to the treble strings is the right channel and the mic pointing to the tail of the piano is on the left of the soundstage. This sounds more realistic to me as a pianist; otherwise it seems backwards, at least compared to the sound I'm used to hearing while playing the piano.

Sidebar:

Should you use more than two mics?

Some recording engineers place many microphones all around and inside the piano. This has the advantage of capturing the character of the instrument and the room acoustic from different locations, plus it allows for flexibility in post production. However, using too many mics can ruin the critical stereo image, which after all is the very purpose of stereo recording. Imagine superimposing several photographs of a scene shot from different angles. The result is a blurry, confusing photo. This can happen to a stereo image too. Some people are more sensitive to a stereo soundstage, while others may feel that the image is worth trading for the flexibility in tone. My engineer in Vienna, Martin Klebahn, has recorded my solo piano albums using two stereo pairs. When used very carefully and skillfully, it's indeed possible to get the best of both worlds, with a stable, well-defined stereo image and a balance of direct and room sound, though it's best to leave this more advanced technique to experienced professionals.

Plugging them in

You’ll need something to plug the mics into. This can be an audio interface for your computer that has XLR inputs or it can be a standalone recorder such as the battle-tested Sound Devices recorders I've used for many years. It should come as no surprise that high-quality preamps will get the most out of high-end mics.

This is way too big a topic to cover here! If you need a starting point, my colleague Maria has written an overview on how to set up a music studio at home that should point you in the right direction.

How does it sound?

Enough theory. How does the Bösendorfer Imperial sound with the Austrian Audio OC818’s using this recording technique? Let’s have a listen.

The first thing that strikes me is the detailed, precise sound. The attack of each note is reproduced accurately, signaling that the ceramic capsules respond immediately to sudden impulses. Slower, less responsive microphones round off the beginnings of notes on the piano. The OC818, by contrast, has a remarkably fast transient response that is needed to record percussion instruments accurately.

This precision carries through to dense passages on the piano, which can overload many microphones. Complex passages with many notes in a tight space, at very soft and very loud dynamic levels, never overwhelmed the OC818’s.

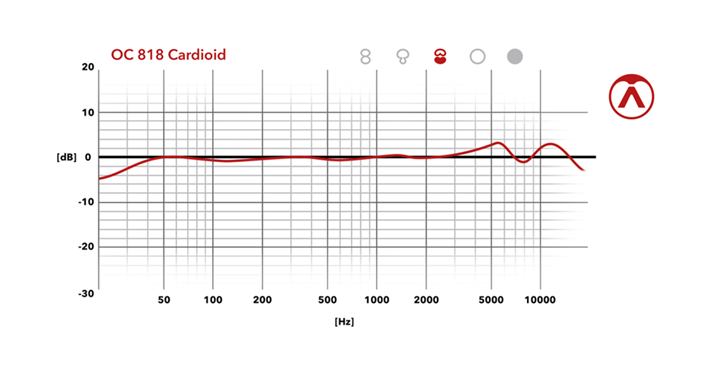

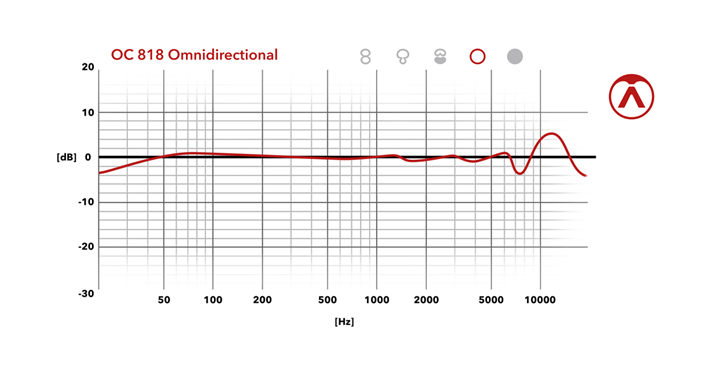

The treble is pleasantly bright, accurately capturing the sheen of the Bösendorfer’s top register, yet never fatiguing. The very low bass sounds tight and punchy yet leaner than the mighty Imperial sounds in real life. Using the mics in cardioid mode could play a role here. As a rule, omnidirectional mics tend to have deeper bass response, and Austrian Audio's frequency response graphs show that the OC818 is no exception, although the difference is minimal.

On the other hand, cardioid mics exhibit a proximity effect that exaggerates the bass if they’re placed too close to a sound source, so the mics do need to be placed at some distance especially from an instrument with powerful bass such as a concert grand. The leaner bass can also be a virtue: Many engineers apply a low-cut (also called high-pass) filter to reduce the deep bass of grand piano recordings in order to reduce pedal thumping noise. Also, keep in mind that the mic input is only the raw material. Similar to editing RAW camera footage, an engineer can tweak the sound to taste.

For comparison, I set up an Earthworks PM40 PianoMic. This system is designed to be installed inside a grand piano. It uses two omnidirectional small-diaphragm capsules that are meant to sound best in exactly the position usually avoided in classical piano recordings, though often used for pop and jazz: very close to the hammers. The capsules are exceptional and make the mics a rare tool capable of capturing even the subsonic frequencies of a Bösendorfer Imperial. They also never sound harsh, even when placed within inches of the hammers. But they are a one-trick pony rather than a workhorse like the OC818's. They’re a serious investment at three thousand U.S. dollars, and well over that here in Europe, making them more expensive than a pair of the much more flexible Austrian Audio mics, which retail for $2500 or € 2200. The capsules are tailor made only for recording grand piano from a position near the hammers. They can’t be used to record other instruments, or even a piano from another perspective.

If you happen to have an application that matches their intended purpose and only ever wish to record piano, they’re a unique, set-it-and-forget-it tool. But if you want maximum flexibility that includes recording grand piano from any perspective inside or outside the piano, as well as most any other instrument, a pair of Austrian Audio OC818’s is a better choice overall. You can make a great-sounding piano recording with either one. If it isn't to your liking, the fault is likely to lie elsewhere in the chain, from microphone positioning to stereo technique, the acoustic, instrument, or preamps. (And let's not forget the player!)

Let’s listen to the same performance recorded with the Earthworks system.

Their frequency response extends into the sub-bass (they are rated to 9 Hz, more than an octave below the lower threshold of human hearing), allowing them to capture the Imperial’s deep bass for which Bösendorfer pianos are famous.

Personally, my biggest surprise came when mixing the mics. After experimenting a bit, my favorite sound came from the Austrian Audio pair as main mics with the Earthworks in a supporting role, filling in some details from a very close perspective. Recorded from these perspectives (with the channels reversed on the OC818 pair), the stereo images are compatible and the mix forms a balanced whole. To my ears, this combination accurately captures the sound of the mighty Bösendorfer Imperial in the studio. That said, the OC818 offers practically limitless possibilities in terms of pickup patterns and placement. I look forward to experimenting with many other configurations, including with different pianos in different acoustics.

Adding a layer of reverb to the OC818’s transforms the studio into a concert hall!

Here is the famous coda of Chopin's F minor Ballade with a comparison of all of the above microphone combinations:

Given this level of sound quality, there's no longer a compelling reason to venture out for on-location solo piano recording. Keep in mind, though, that this is an acoustically treated studio with a concert grand. The acoustic treatment makes a night-and-day difference. A different piano in a different acoustic played by a different pianist will inevitably sound very different.

Recommendations and conclusion

If you’re a serious pianist, it’s worth investing in at least one high-quality microphone. A pair configured in a standard stereo technique such as ORTF will allow you to record your playing and listen back in high fidelity. A word of caution: Professional microphones are like taking a microscope to your playing. You’ll hear every detail of timing and articulation, for better or worse. If you use high-end mics such as the Austrian Audio OC818 heard here, they’ll pick up every nuance of your playing. This may be a double-edged sword, but it is bound to inspire you to keep improving.

These mics are meant for professional studio recordings and they’re designed for maximum flexibility, so they may be overkill for some. If you know you’ll only need a directional (cardioid) mic, Austrian Audio also makes a junior sibling, the OC18. This model lacks switchable pickup patterns, dual output, and Bluetooth, but it has the same high-end sound using the same handmade ceramic capsule and it can still be used for many different instruments and vocals. They also make a cardioid small-diaphragm condenser, the model CC8, which I have yet to hear. It costs about a third of the price of the OC818. Since it is tuned to the same extremely tight specifications, you could always get one now and add another one later, another unique feature of Austrian Audio microphones. Finally, keep in mind that the ORTF stereo technique will work with any two directional mics. Ideally they should be an identical matched pair.

As for the classic Viennese sound, Bösendorfer and Austrian Audio are a match made in, well, Austria.

Start Your NEW Piano Journey

Sign up below and each week for the next year, I'll send you a conservatory-quality 3- to 5-minute lesson sharing exclusive playing and practice techniques used by concert artists worldwide.

Each lesson has been carefully crafted to meet the needs of players ranging from beginners to the late intermediate level.

As a very special bonus, you'll also receive invitations to join our exclusive live Keys to Mastery™ monthly masterclasses.

We will never sell your information, for any reason.